Brian and Eileen Keelan live in their 10-foot flatbed Alaskan Camper in pursuit of native plants, mammals and birds across the United States, Canada and the world. And sometimes, the native species pursue them. Hey Bear!

What is a naturalist? While we had heard the term before, we never really understood exactly what a naturalist was until researching for this article.

In a nutshell, a naturalist is a person who directly observes and studies plants and animals in their natural environment. For example, Charles Darwin and John Muir are two of the most famous naturalists in history. Darwin’s species categorization and research allowed him to formulate science-based explanations about nature. Muir’s groundbreaking work in conservation helped found our current day National Park system.

Do you like understanding the world around you and the National Parks? Then you dig naturalists. And if you enjoy observing nature, you’re also something of a naturalist. Put us down on both counts.

What better tool for a naturalist than a go anywhere, camp anywhere truck and camper rig? After a different sort of observation, research, and study, that’s exactly what Brian and Eileen Keelan concluded. Two Alaskan Campers later, they have retired, dubbed themselves the ‘Nomadic Naturalists’, and devoted their time to the pursuit of native plants, animals, and birds across the American continent and the world.

Their current custom 10-foot flatbed cabover Alaskan Camper was designed as a mobile naturalist laboratory and observation blind. Everything from the larger windows to the canoe loading system to the size and type of storage was chosen to maximize their work in the field, and full-time comfort.

But don’t get too comfortable. All of that time in wilderness locations has resulted in some close encounters with their subjects, and whatever else wanders into their remote campsites. From a Black Bear to a deermouse, they’ve had company.

Above: Brian and Elaine’s current rig, a 2021 Ford F350 and 2016 Alaskan 10-foot camper dry camping, Pawnee National Grassland, Colorado

Where did your passion for natural history come from?

Brian: My mother loved natural history, having worked as General Curator at the Boston Museum during World War II. She tried desperately to interest my older sister in nature, but no luck. The same happened with my older brother. She realized that you can’t force an interest, but you can encourage it. When I came along, she did not try to steer my interests. Ironically, at age seven, I got very close to a beautiful pair of American Goldfinches, and that started a lifelong passion for natural history.

Above: Scarlet Hedgehog Cactus, Echinocereus coccinea variety rosei, El Paso County, Texas. The Trans-Pecos region of Texas has the greatest diversity of native cacti in the U.S. This species can form mounds containing scores of individual heads.

Today we spend the most time searching for native plants in the United States and Canada, but we also actively pursue mammals and birds, especially on tours to international destinations. We also identify as many butterflies, reptiles, amphibians, dragonflies, and damselflies as we can, mostly from photos.

Eileen: Brian saw a pair of Goldfinches which sparked his interest. About twenty years later, I saw him and that sparked my interest. I’ve always enjoyed the outdoors and wild places but I had not studied natural history before we met.

What did you do professionally before going full-time in your Alaskan Camper?

Eileen: I was a teacher with certification in secondary social studies. I’ve always been interested in history and developed a special interest in the Civil War. Wherever we travel, I look for historical sites.

Brian: After getting a Ph.D. in Chemistry, I worked as a research scientist in the imaging industry for 30 years, with 20 years at Kodak in Rochester, New York, and 10 years in Silicon Valley. It was an exciting field to be in. During my career, the world of imaging made a complete transition from film to digital, and so I got to do research on many different technologies. My years at Kodak led both Eileen and me to develop strong interests in photography, which continue to this day and are an integral part of our field work.

Above: Their website, Nomadic Naturalists

What is Nomadic Naturalists?

Brian: Nomadic Naturalists is our blog, which we started when we retired in late 2016. It was primarily intended as a way for our friends and family to keep up with what we were doing, and for us to capture memories and record our thoughts as we traveled. A small number of people also follow it for natural history and travel information. Eileen takes the photos and I write the prose. We typically post about ten times per year.

What originally led you to Alaskan Campers?

Brian: In October 2001 we took a trip to Montana in our van so Eileen could attend a week-long workshop on mammal tracking. While she was doing that, I stayed in the Many Glacier area of Glacier National Park, enjoying sightings of Grizzly and Black Bears, Bighorn Sheep, and Mountain Goats. The camping was truly brutal at that time of year.

We had always planned when we retired to buy a camper and travel extensively. On the three-day drive home, we discussed why exactly we were going to wait another decade or more to be comfortable. So we started doing research into the different types of campers (including RVs) that were available and kept coming back to Alaskan Campers. They seemed perfect for the sort of remote camping we liked to do.

The advantages of pop-ups are well known and appreciated; less wind resistance and noise, better clearance, better gas mileage, and lower center of gravity for handling. As ardent flatwater paddlers with a 17-foot Kevlar canoe, the most important factor was that it can be dramatically easier to get a canoe or kayak on and off of a pop-up roof.

We currently use a Thule Hullavator bolted onto our boat rack, and are able to get our canoe on or off in about six minutes without using a ladder! This allows us to paddle any time we find an interesting spot, without hassle.

A hard-walled pop-up camper was very appealing compared to soft-walled models. Having real windows, better insulation from heat and cold, and less maintenance were all important pluses.

We ordered our first Alaskan Camper, a 10-foot cabover model, a few months after the Montana trip and drove our new pickup truck across the country to have it installed the following summer. We used that Alaskan Camper for 13 years, spending over 900 nights in it, despite working full-time.

Above: Eileen with their first Alaskan Camper, in Anza-Borrego Desert Sate Park, California

Eileen: Prior to getting our first Alaskan Camper, we tent-camped for years. Eventually, we moved on to a cargo van, and then a family-style minivan that we rearranged the insides of to accommodate our camping gear and sleeping space. We moved away from tent camping because some of us believe that we are surrounded by bears at night. Even after all these years, a truck camper feels luxurious.

The trips in our first Alaskan Camper were on annual vacations, usually about three weeks, and on weekends. During those annual trips, we’d visit a part of the country, say the Four Corners area in the West or the Rockies, and do a sort of survey, studying the natural history and history of that area, and doing a lot of photography. The weekend trips were, of course, much closer to home.

Some of our favorite places to camp were the Adirondack Mountains in upstate New York, where we did a six-year plant study of a 200-square-kilometer site centered on the Moose River Plains, censusing and identifying over 500 species. The year after our study was complete, we helped locate or relocate rare plants in several state parks. We also spent a lot of time in Ontario; photographing, canoeing, and, as always, looking for birds, plants, and mammals.

We especially like dispersed camping, enjoying the solitude and quiet of natural places and wilderness. National Forests and Bureau of Land Management (BLM) areas, as well as parts of some large national parks allow dispersed or backcountry camping. State Parks are often designed to allow you a slightly more natural experience while still in an organized campground, with a little extra space between sites, and trees or other vegetation between you and your neighbors.

Above: Rick Bremgartner and Bryan Wheat with Eileen and The Big Ol’ Truck II, at the Alaskan Camper factory in Winlock, Washington

Please expand on how you went about designing what you wanted in your second Alaskan Camper. Was there a list?

Brian: Our first Alaskan camper was truly wonderful, and we really appreciated how Bryan Wheat, President of Alaskan Campers, was always so gracious about answering questions and helping out when we needed advice.

We needed a lot more storage space for full-timing when we retired. After thoroughly analyzing the possible options, with help from Bryan, I decided that a custom flatbed unit was the best alternative.

Above: Their first F350 chassis cab as it arrived from Ford. It is possible to put a flatbed on a pickup with the bed removed, but the chassis cab provides a longer cab to axle length and straight rails for a cleaner attachment of the flatbed.

There are some significant disadvantages of flatbed units. First, the market for used flatbed trucks and especially used flatbed campers is small. They are neither easy to buy nor easy to sell. Second, it is a significant operation to transfer a flatbed camper to a new truck. The flatbed itself has to be detached from the old truck frame and attached to the new truck frame. We are on our fourth truck under Alaskan campers, and likely will go through a couple more, so this is not an insignificant factor for us.

Above: This was taken the same day as the previous photo. Eileen on the flatbed after the attachment of the custom aluminum flatbed by Pro-Tech.

However, a custom flatbed unit provides a great opportunity for creating more and better storage. Furthermore, it is structurally strong because there is no overhang; the side walls are straight vertical and directly supported by the flatbed.

The challenge is how to use the extra volume created by having no pickup bed rails or wheel wells, to create genuinely useful storage space. I spent hundreds of hours researching how this might be done; making measurements on our standard (non-flatbed) Alaskan; drawing up plans; talking with Bryan; getting advice from Aaron Tyger of ProTech, who constructed the aluminum flatbed through an agreement with Alaskan Campers; and ultimately producing a spreadsheet of specifications with 55 line items. This somehow was turned into a camper by Bryan, Rick Bremgartner (Alaskan’s Foreman), and their team.

Above: Camper showing part of storage system enabled by the flatbed design, Johnson Lake State Recreation Area, Nebraska.

How is the new Alaskan Camper better for what you’re doing?

Brian: Although our new Alaskan Camper was the same size as our first, we did end up with an amazing amount of truly convenient storage. We store most of our stuff in Rubbermaid Roughneck 10-gallon bins. In the new camper, we have room for ten more 10-gallon bins than in the old one, and every bin is easily reachable.

In addition, we have two aluminum boxes on the underside of the flatbed, providing even more storage space. When we are on the road, every bit of storage is used, and we are exactly at our gross vehicular weight rating of 11,300 pounds. This capacity has allowed us to stay on the road for a year at a time, without visiting our tiny storage cube in El Paso, Texas to exchange gear and reference books. This is a pretty remarkable capability in a single rear wheel truck.

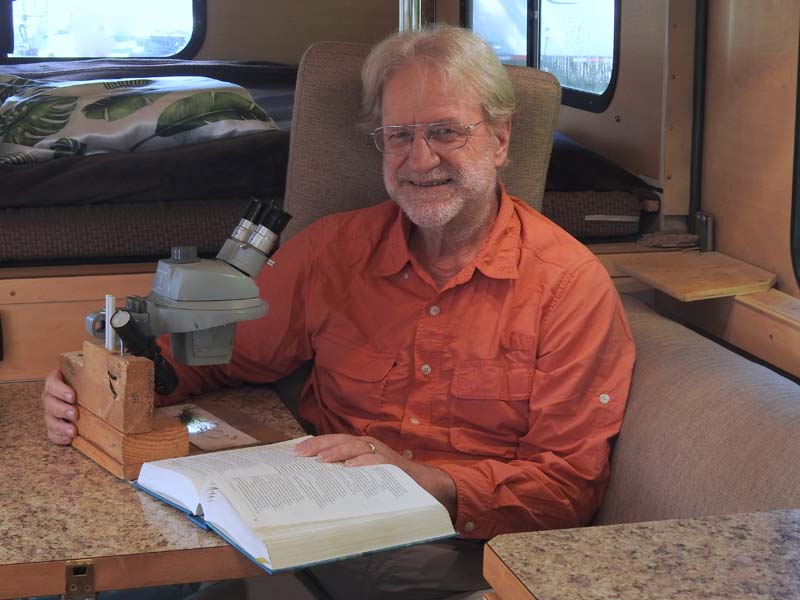

Above: Brian identifying a plant specimen using a stereoscopic microscope and a technical reference book containing all the 4000+ vascular plants of Florida — 800 pages but no pictures.

We made a number of other enhancements as well. When in camp, I spend quite a bit of time inside the camper, using a microscope to identify plants, working on our laptop, etc. I want to feel like I am outside, hearing birds singing, feeling the breeze, and enjoying the view. So we requested extra windows on the sides, and larger windows in the cabover, and oriented each window screen for the best possible acoustics and airflow. The result is marvelous; with the windows open, it’s almost like being outside, and we have a panoramic view of our surroundings.

Eileen: In our first Alaskan Camper, a hose drained the sink into a plastic container outside the camper. A raccoon vandalized it one night in the Everglades and we got in trouble with the ranger, so we had to figure out a better way. Bryan Wheat said he could include a removable grey water tank. This has allowed us to camp in a number of places requiring that campers be self-contained.

Above: Their rig as it looks today, Camper #2 on Truck #4; two full spare tires, one on the front and one on the back for travel in remote areas such. Although roof space is at a premium because of the canoe, there’s a solar panel, air conditioner, fan vent, and cell booster antenna squeezed in between the boat rack cross-members.

The new Alaskan also has an awning that allows me to be outdoors even when it’s raining. With the camper so small, it is good to be able to expand the living room to include the outdoors.

Some other enhancements were a water heater for the outdoor shower and, after a year and a half wait due to COVID-related supply issues, an air conditioner.

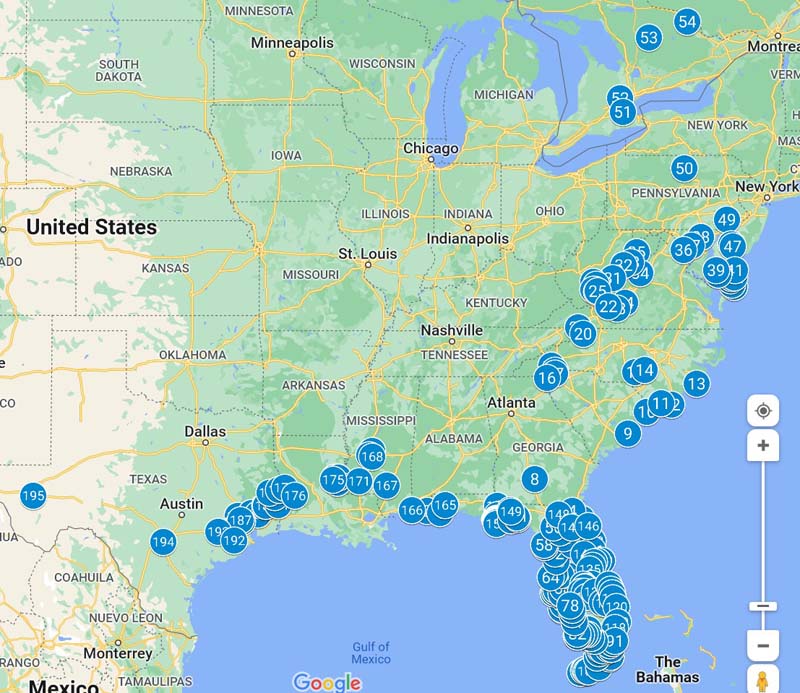

Above: A Google Map showing the locations they are visiting in 2022. Most of the nearly 200 sites are places they are searching for particular plants.

How do you plan where to go, and when to be there?

Brian: I do intensive research over the winter to plan our route, which is different each year. Since retiring we’ve taken the camper to all 49 continental states and most of the Canadian provinces and territories. We would have reached them all if it were not for COVID.

Above: Coatimundi, Chiricahua National Monument, Arizona. Coatis principally occur in southeast Arizona and Mexico, and are in the same family as raccoons. They sometimes are seen in large groups.

The itineraries are based on a combination of looking for particular species (often rare or unusual native plants), visiting interesting sites, experiencing special phenomena like bird migration or a total eclipse, exploring regions in depth (such as five months spent focused on prairies), and doing high-quality paddling.

All my notes are contained in a single PDF file with coordinates for every site to be visited (typically a couple hundred per year). These coordinates are also plotted on a Google Map with sites numbered in the order we’ll visit them. Once we’re done at one spot, we can just click on the next number on the map, refer to the PDF file for details, decide if we still want to visit it and navigate to it.

Unless reservations are needed, we usually don’t plan where we will camp to maintain flexibility in our schedule.

Above: Brian in their canoe just identified their ten thousandth species (Allium schoenoprasum), Waterton Lakes National Park, Alberta

That day-to-day flexibility is ideal. How do you determine what research to conduct?

Brian: We usually have projects or goals toward which we are working. One major effort was for me to see ten thousand native species of plants and animals. I finally reached this goal on September 2nd, 2019, finding a wild onion, Allium schoenoprasum, while canoeing in Waterton National Park in Alberta, Canada.

One current project is for us to locate as many native families and genera (plural of genus) of vascular plants (ferns and up) in the continental United States and Canada. To date, we’ve found all but two of the 239 families, and about 83-percent of the 2,100+ genera. We’ve challenged ourselves to see all the families, and 90-percent of the genera.

Above: Purple Gallinule, Anhinga Trail, Everglades National Park, Florida. This colorful bird occurs in the southeast U.S. and Middle and South America. It likes fresh water habitats with floating vegetation such as the water lilies in this photo.

Eileen: On a recent morning, we got up at 6:30am, ate breakfast, and left camp. We had a reservation to take an early tour boat excursion in Everglades National Park. According to Brian’s notes, a plant we were interested in was visible from the boat. We asked the tour naturalist to point it out. He also pointed out a crocodile. We saw dolphins swimming near the boat, Ospreys and White Ibis flying overhead, bromeliads and an orchid on mangrove branches at the edge of the water.

When we returned to the dock, we decided we’d like to see the plant up close so we packed a lunch and set off in our canoe. We would paddle to the plant location, admire them, take some photos, eat lunch, and paddle back. The first time we paused to look at something among the mangroves, we were swarmed by mosquitoes in spite of anointing with repellant before setting out. Not long after that, it began to rain and we were soon soaked. When we reached the place we had planned to have lunch, we instead unloaded the canoe and turned it over to empty it of at least five gallons of rainwater. When the rain began to let up, we set out again.

After finding the plant and taking photos, we decided to escape the mosquitoes in the mangrove corridor we were in and continue out into the open bay. There was a light breeze, and we ate lunch in the boat. When thunder began rumbling again, we paddled the three or so miles back to the dock, put everything away wet, and drove back to camp where we spread it all out to dry. After dinner, Brian studied the photos and the guide to Florida plants and determined that we had indeed found the plant we wanted to see.

Most days we don’t need to set an alarm. We may have a short drive to our location (if possible we camp no more than an hour or so drive away). If we’re lucky, we can walk from camp. Sometimes we can drive right up to the plant, but often there is a hike.

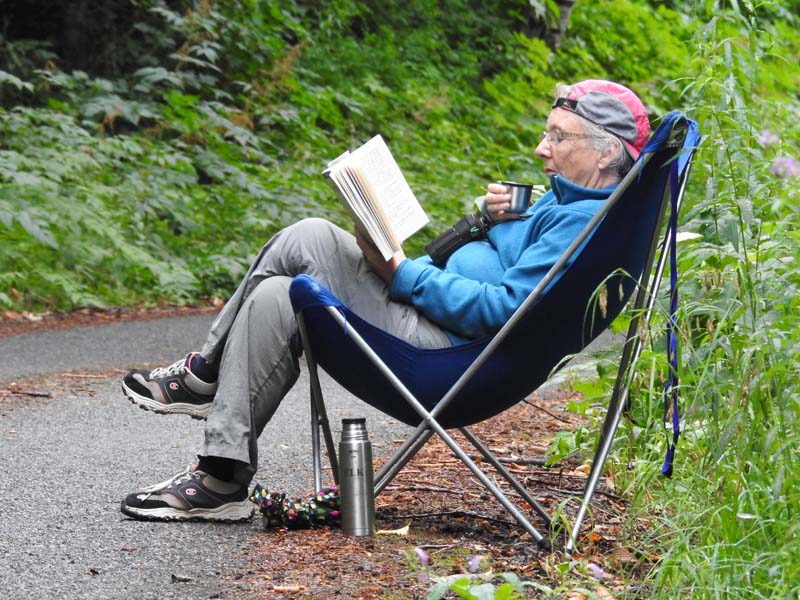

Above: Eileen settled in for a long (and unsuccessful) stake-out of a burrow made by an Aplodontia, a primitive rodent; Lolo Pass, Mt. Hood National Forest, Oregon

Depending on the length of the hike, we’ll either bring lunch with us or return to the truck and make sandwiches. A single plant search can be an all-day affair or we may visit several locations in one day. We try to plan the day so that we can return to camp before dark. In the evenings, we work on identifying the plants, sort photos, relax, read, etc. Occasionally, we watch a DVD movie, TV program, or documentary on the laptop.

Every once in a while, we spend the day in camp, either to take a day off from all the hiking, paddling, birding, and botanizing thrills or to catch up on emails or laundry, write the blog, keep in touch with friends and family, do camper maintenance, etc. We try to time most shopping trips with days when we have a long drive to our next location.

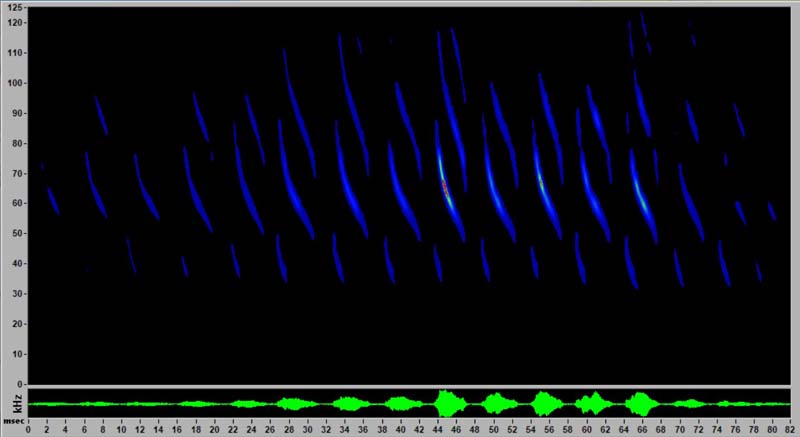

Above: Riverside County, California. Recording of echolocation calls of California Leaf-nosed Bat, made with an ultrasonic microphone. The horizontal axis is milliseconds, with the (relatively) long gaps between calls removed. The vertical axis is kiloHertz (kHz); the calls range from about 30 to 120 kHz. Humans cannot hear anything above 20 kHz, so, like most bats, these are inaudible.

Has owning an off-road and off-grid capable truck and camper allowed you to get closer to the plants and animals you’re researching?

Brian: Yes. The truck camper enables us to camp in remote and beautiful areas, which are often very interesting for natural history. For example, near the Colorado River in southeast California, we were able to reach, via a repeatedly washed-out road, an abandoned mine with a population of California Leaf-nosed Bat.

This is a very difficult species to see in the United States. From the convenience of our camper, we set up our ultrasonic recording equipment, and half an hour after sunset, we were surrounded by this species as they foraged, sometimes approaching within fifteen feet! It was a magical experience, and we obtained high-quality recordings of their echolocation calls.

Above: Yellow-faced Pocket Gopher, Baca County, Colorado. Photographed from their cabover, while watching Lesser Prairie Chicken mating displays at a lek.

Once we were passing through southeast Colorado in early May at just the right time to see the spectacular dawn mating displays of Lesser Prairie-Chickens. It is critical not to disturb the birds during these communal displays, so you need to set up in the dark and wait quietly until after they have finished, usually an hour or two after dawn.

We were able to drive up to their mating grounds (called a lek) the evening before and set up the camper so we could use it as a blind the next morning. Before dawn, we carefully lowered one wall of the cabover and then waited in the comfort of our sleeping bag for the show to begin. We had a great viewpoint from seven feet above ground level, looking down on the displaying birds! A bonus was a Yellow-faced Pocket Gopher that periodically came out of its burrow to feed on vegetation; it’s the only time we’ve seen this shy prairie species.

Eileen: Speaking of animal stories, in September 2020 we were in Minnesota looking forward to spending the month canoeing. We enjoyed watching the leaves change color, the berries ripen, and the animals get ready for winter.

One cool afternoon, I wrapped up in blankets and was sitting outside reading while Brian was doing something important inside the camper. I placed my chair next to the rear tire to block the breeze coming from that direction. A White-tailed Deer snorted and I looked up to see a doe and her fawn emerge from the shrubs across from me and run off.

As I returned to my book, something else caught my eye and I glanced over to see a Black Bear standing next to the rear steps of the camper, about nine feet away (we measured the distance later). He was definitely one of those animals getting ready for winter, as he was large and had a thick, shiny coat of fur.

After a few moments, I thought I should let Brian know about our visitor. The bear was not looking at me but I also thought I should say something to him, just to be polite. So I called out, “Hey bear,” loud enough for Brian to hear but in a friendly voice, for the bear. From the camper, I heard Brian’s reply. “Pardon?” “Hey Bear!” The bear began walking across the dirt road but Brian got out in time to see him before he disappeared, probably heading off to finish those berries. I know he was thinking something polite too, like, “It was nice meeting you. Enjoy the rest of the autumn.”

Some animals have been pretty interested in the camper itself. An Eastern Phoebe started constructing a nest under the flatbed while we were camped for a couple of nights in Oklahoma. A Northern Flying Squirrel landed on our roof in Maine with a soft thump, and then peered down through the fan vent, giving us quite a good look. But the animal that made himself most at home was a deermouse (genus Peromyscus).

One weekend we were camping in southern California. We had just arrived on a Friday evening and we were getting settled in when I went looking for something in the cupboard that is just above my usual seat in the camper. These cabinets are hinged at the top and when I raised the door, what sounded and felt like, about five pounds of dry pasta came tumbling out. Turns out “only” a pound of pasta spirals rattled out and scattered all over the place.

We investigated the closed food box in the closed cabinet where the pasta was supposed to be and found the empty bag that had been chewed open. The contents had been transported from a lower cabinet on one side of the camper to an upper cabinet on the other side. We had several sightings of the deermouse scampering around over the next couple of days and finally caught him in a live trap. We probably should have used pasta for bait.

He liked his comfortable arrangements and, when we tried to release him, he would not come out of the trap. I was down on the ground giving him some encouragement. You know, ‘time to get a place of your own’, “start supporting yourself instead of relying on us,” etc. He emerged from the trap – and hopped into my lap. He eventually scampered away but I’m wondering if we are expected to visit once Pasta Mouse starts a family of his own…

Above: The interior of their second camper, from the cabover to the back door.

Not too many people have attempted to live full-time in an Alaskan Camper. How has that worked out?

Brian: As background, I retired in September 2016. We had already sold two vehicles and emptied the house, donating or throwing away nearly everything we owned. We drove our one remaining vehicle and a small U-Haul from California to El Paso, Texas, and our realtor sold the house. We rented a 4 by 8 foot storage space and lived on an extended stay facility while changing domicile and waiting for our new chassis cab, months overdue, to arrive. It was finally completed in November but then was “lost” for 42 days somewhere in the Kentucky Ford facility. We finally started full-timing on February 27, 2017, five months after retiring.

Above: Camper interior panoramic showing custom windows from eye level when seated. These give a great view, light the interior nicely, provide extra ventilation, and allow them to hear birdsong and other ambient sounds well.

Eileen: We love full-timing! It is more a lifestyle than a vacation but, like a vacation, it involves a high percentage of time being devoted to things that are fun or interesting. We managed to take two 52-day trips during our working years by accumulating multiple years of vacation. So we had a clear idea of the challenges and experienced no real surprises.

Some aspects of full-timing are easier than living in a home, some are more difficult. You have to locate everything at each new campground – restrooms, showers, laundry, trash disposal – and figure out how to operate them. You’d be amazed at how many models of washers and dryers there are and that no two campgrounds or laundromats have the same one. Most still use quarters. That probably started during the last ice age when a load didn’t take more than one or two quarters. These days you have to feed twelve or more quarters per load into the washer and dryer. Some places will take a credit card which is the most convenient method, although the process can vary. One recent one required us to download an app or buy a card and download the funds onto it. It took about 40 minutes to follow the, “three easy steps.”

Above: The interior of their second camper, looking forward from inside the back door. They added the upright cushions as backrests, so they could sit sideways on the dinette seats; they fold down for travel.

On the other hand, less room to live in also means less room in which to make a mess. Having less stuff means there is less stuff to take care of, clean, put away, or make decisions about. We only have to sweep the floor with a whisk broom. Driving on dirt roads collects a bit of dust but it doesn’t take long to wipe down the few surfaces we have. And we have a built-in nudge to be clutter-free: since the Alaskan camper’s roof must be lowered whenever we drive, the bed in the cabover is always made and nothing is left on the countertops. We run through a checklist when closing down to be certain that everything is put away, closed, or turned off.

Full-timing has become easier with practice, but one key aspect has become more challenging in recent years; many campgrounds are now fully booked so far in advance that the flexibility of the nomadic lifestyle has been substantially reduced in many regions at desirable times of the year.

Above: Camping among pillars of volcanic tuff in City of Rocks State Park, New Mexico

We have experienced that as well. How have you adapted to these challenges?

Eileen: We left El Paso in February of 2020, shortly before shortages and quarantines began. Like everyone else, we had difficulty finding toilet paper, hand sanitizer, and our own preferred brands of certain foods, like peanut butter, cereal, and pasta sauce.

Because we were traveling, we rarely shopped in the same place more than once. One of our first adaptations was to use whatever brands were available rather than looking for what we thought we preferred. However, even before stores put limits on the number of items you could buy at one time, we didn’t stock up on very many things because we don’t have the storage space.

Campgrounds began to close. We were fortunate to be in the West early in 2020 and could take advantage of BLM areas where dispersed camping is allowed. Campgrounds that did remain open, often closed their facilities including not only visitor centers and campfire circles, but also restrooms and showers. And it became difficult to fill up on water and propane.

BC (Before Covid) we had planned to return to El Paso in November. Each previous winter after retirement we had spent a couple of months in an extended stay facility (basically, a motel room with weekly and monthly rates) in El Paso, giving us a chance to visit with my family, do research for the next year, and take birding tours to international destinations.

In November 2020, El Paso was dealing with an overwhelming number of cases; hospitals were full and patients were being airlifted to other cities. By then we were in south Texas and decided to move on to Florida instead. We spent most of the next eight weeks camping and canoeing in the Florida Keys and the Everglades. Aside from COVID worries and missing the family, we were able to enjoy the somewhat spontaneous new plan.

Brian: One challenge during COVID was buying a new truck and transferring the camper to it while on the road. The transfer is best done by an upfitter, and these are few and far between. Before even ordering our flatbed camper, I had corresponded with an upfitter in Fort Worth, Texas (AutoTruck.com), to learn about the process. They had a Ford dealer just minutes away, Five Star Ford, where the Fleet Manager, Mike Minardi, did a great job ordering the chassis cab and obtaining bids on our current truck based on photos we took. Once the truck was shipped from Ford, we left Florida and found a motel in Fort Worth where we could park right outside our door.

It took a day to remove everything from the old truck and put it in our room – it’s amazing how much an extended cab will hold (we did not have to remove anything from the camper itself). The next day we drove to the dealer, completed the paperwork, and formed a four-vehicle convoy to the upfitter: Mike drove the new truck, I drove the camper, Eileen drove a rental, and an associate of Mike’s drove another vehicle to bring him back. What great service!

AutoTruck.com finished the transfer, including all wiring and a front-mounted spare tire, in two-and-a-half days and it cost about $2,400. Five Star Ford picked up the old truck directly from the upfitter once the camper had been removed, and then we picked up the camper on the new truck, and spent the rest of the day loading the truck. Everything went like clockwork, and the entire process took five days.

Above: Eileen poses next to sauropod dinosaur tracks in Picketwire Canyon, Comanche National Grassland, Colorado

Do you have any advice for someone considering full-timing in a truck camper?

Eileen: Consider why you want to do it. We already had hobbies and interests that work well with full-timing. And we were happy adapting from living in a house to living in a much smaller camper. For example, most of our meals don’t have long ingredient lists and we don’t often plan for leftovers; except for pizza, of course.

As mentioned earlier, you still have the same chores you did in a house; pay bills, cook, clean, wash dishes, do laundry, take out the garbage, go shopping, etc. But most of those things can be done on your own schedule. I don’t have to make sure the garbage is at the curb by 6:00am every Tuesday. Rather than a garbage can, we have a very small waste basket. It has to be emptied frequently and I have to locate the dumpster in each new campground. I’m okay with that. You figure those things out as you go.

For a weekend or a couple of weeks of vacation, sleeping late and hanging out at your campsite or at the beach sounds relaxing. You may need a little more than that for this lifestyle to be fulfilling long-term. Knowing that it is not necessary to abandon all your hobbies and interests can help make the decision.

Brian: Before making critical life decisions and expensive purchases, we’d recommend a serious test trial emulating the lifestyle you hope to adopt. A truck camper is a pretty small platform for full-timing even for one person, let alone a couple, and it is difficult to envision what it will be like without trying it. There are truck camper rentals available in Alaska, a fine region in which to spend a couple of months seeing what it could be like.

If you do decide to full-time, you should investigate Escapees, Inc. They provide mail-forwarding and a legal address in the only three states that allow full-timers to domicile without a non-commercial address; Texas, Florida, and South Dakota. Establishing proper domicile is a tricky legal issue for full-timers, and it can have major consequences if not done properly.