Faced with shut downs and cancellations due to Covid-19, independent filmmaker, Kris Millgate, quickly adapted her production plan and set out alone in a Toyota Tundra and a Four Wheel Camper. The Chinook salmon were not going to wait.

Above: Outdoor journalist, Kris Millgate, followed the Chinook salmon’s migration 850-miles from the Pacific Ocean to Idaho while living and working out of a truck and camper during a pandemic. Photo Credit: Tight Line Media

Trailblazing wildlife naturalist, Kris Millgate, graduated from the University of Utah in 1996 and went to work for television news networks. Ten years later she founded Tight Line Media, a content production company focused on outdoor writing and filmmaking.

Through Tight Line, Kris produced for PBS affiliates and articles for USA Today, Field & Stream, and East Idaho Outdoors. Late last year, she vividly recounted her experiences of becoming a respected outdoor journalist in her published memoir, “My Place Among Men”.

All of these achievements seem like a preamble for the struggle to create, “Ocean to Idaho”. After months of careful planning, the project was about to begin when the Covid-19 pandemic struck. With hotels closed and restaurants shut, Kris’s meticulously prepared production schedule and all-important crew had to be completely recalculated.

Would Kris cancel her dream and wait until next year? Absolutely not. She pushed on and made some very clever changes. In fact, we wouldn’t be bringing her story to you if it weren’t for the pandemic, and what she did to adapt to it.

Unable to stay in hotels and eat at restaurants, Kris got the idea to use a truck and camper. With a truck camper rig, she would have a safe place to sleep, a safe place to store film gear, and have all the food, water, and provisions required.

In a nutshell, Kris would be fully self-contained, socially-distanced and 100-percent mobile. On paper, it was perfect. Now all she needed was a truck, a camper, learn how to use it, and, with many campgrounds closed, find places to camp along her route. And the Chinook were coming.

Naturally, Kris triumphed in the face of these challenges, but that’s nowhere near the whole story. The whole story, including the genesis of her film project and the unbelievable places it took her, is something you have to read in her own words. Let’s just say there was more than salmon swimming upstream.

Once completed, “Ocean To Idaho” is set to publish as a print and video story in 2021. We’ll keep in touch with Kris and announce the air dates. After learning her account, and the compelling film she has just produced, you won’t want to miss it.

Above: Ocean to Idaho, The Route

What is the Ocean to Idaho Project?

Ocean to Idaho is a social media and feature film project that follows the Chinook salmon’s annual migration from the Pacific Ocean in Oregon to central Idaho. It’s an unbelievable 850 river mile journey through three states and four rivers.

Most people don’t know that Chinook salmon return to where they are born. The idea that a wild animal can do this, and the possibility of following this incredible migration was very compelling.

Above: Outdoor journalist, Kris Millgate, is also a trail runner and a fly fisher. Her fly rod only revealed itself once during the production of Ocean to Idaho, but not for salmon. Fishing for salmon, which are threatened and endangered, is extremely limited and non-existent in some places due to the low population counts. Millgate tried for trout on the Salmon River but left with an empty net. Photo Credit: Tight Line Media

Where did the idea for Ocean to Idaho come from?

I’ve covered outdoor natural resources for more than two decades. I started in television and then added newspapers and magazines. There are a lot of outdoor stories here in Idaho because a lot of Idaho remains an undeveloped country.

In central Idaho, there is a spot called the Yankee Fork, a tributary of the Salmon River. In 1940, New York investors built a 988-ton gold dredge in the Yankee Fork that operated into the 1950s. Now abandoned, the dredge is still there.

The dredge and its operation significantly impacted the Yankee Fork and turned the river upside-down. Turning the river upside-down ruined it for wildlife and fish.

Above: Ocean to Idaho, Mile 828

Thankfully, there’s a big restoration project for the Yankee Fork that will take decades to complete. In 2016, I took a look at the restoration work and did a story on how they put the watershed back together. Each year, a dwindling handful of salmon make it back to that river.

While I was there, I saw a Chinook salmon on a spawning bed. I was looking at a wild fish that was born in Idaho, was flushed out to the Pacific Ocean, and then swam back against the current to the Yankee Fork. I knew after she laid her eggs, she would die.

I watched the Chinook and said to myself, “How remarkable”. The idea for Ocean to Idaho blossomed from that moment. By sharing the Chinook’s journey from the Pacific Ocean to central Idaho, these wild animals and places could mean more to people.

In the Pacific Northwest, people have a special connection to the Chinook. They know what it’s like to fish for Chinook. I have seen people cry because they know that they’re not coming back much anymore.

Above: Kris pushed forward and safely completed her project even after Covid changed her original plans. Photo Credit: Tight Line Media

How did plans come together to follow the Chinook’s migration?

The Ocean to Idaho Project needed to happen in June when the Chinook start the migration process. In my book, “My Place Among Men” there is a chapter about the end of the Chinook’s migration. This time I wanted to show the entire journey and not just the conclusion. At least that was the plan, until Covid struck.

I had to dump my hotels, flights, and crew because of Covid restrictions. Luckily, I know how to make a film on my own. To pull this off safely and responsibly, I had to be fully self-contained. Even with Covid, I was determined.

The virus dominated everyone’s attention, and I wanted to show something else. Maybe the Ocean to Idaho Project and the remarkable perseverance of the Chinook salmon could help us all through a crazy year.

Above: Salmon must clear eight dams before they reach the Salmon River in central Idaho. The Ocean to Idaho rig, parked along the Salmon River, is a Toyota Tundra outfitted with a Hawk edition pop-up camper from Four Wheel Campers. Photo Credit: Tight Line Media

How did you put a truck and camper rig together by the June start date?

At the time it seemed overwhelming and impossible, but I tend to gravitate towards immense challenges. In May, I wasn’t sure the project was going to happen, but I kept my interviews scheduled. Despite Covid, everyone remained all-in.

Knowing that the Chinook salmon start moving in May and that I might not have a way to get to them was immensely frustrating. If I missed them, I would be out for another year. The numbers on salmon populations are terrible and there are only so many years to do this before it could be too late. I did not want to delay.

The way Toyota got involved began in 2019. On the same day that I launched my book tour in August, my 12 year old truck died. I have always bought vehicles from Teton Toyota, and went there to look at trucks.

They told me they had bought my book and asked how the book tour was coming together. They also asked me what’s next and we started discussing a partnership project.

I’m not the usual Toyota partner, but its truck customers love fishing, hunting, and outdoor activities. When I told Toyota that I wanted to follow the Chinook salmon from the ocean to Idaho, they were genuinely interested.

When I added my social media presence and that I was going to pull this off safely during the pandemic, Toyota had a compelling element to get involved with.

“Maybe the Ocean to Idaho Project and the remarkable perseverance of the Chinook salmon could help us all through a crazy year.”

How did you Four Wheel Campers join the project?

Having my camera gear in the back of the truck and sleeping on the side of the road was not going to be comfortable or safe. With that in mind, I reached out to Four Wheel Campers and told them what I was trying to do.

I explained that I wanted a safe, secure, and comfortable place for me and my gear. They jumped in and had a camper lined up. With the pandemic, trucks and campers were in low supply. I was fortunate to have both available.

Before this experience, had you owned or used an RV before?

Yes, I own a travel trailer, but this was the first time I used an RV by myself. I had a crash course with Four Wheel Campers about how it worked. I left the next day and drove several hundred miles to the Oregon coast.

Why didn’t you take your trailer?

A trailer was not going to accommodate the off-road conditions or tight turnarounds necessary for where I would be going. I would be camping in non-traditional places and didn’t want to be in an RV Park two-feet away from others.

By the end of the journey, I wasn’t on paved roads. I had to be able to put my truck in four-wheel drive to reach the places I needed to go in central Idaho. Plus, I was only one person, so I didn’t need the space of a trailer.

When I was in Oregon with Idaho plates, people thought I was on vacation. With Covid spreading, they were not exactly thrilled to see me. That became another reason a truck and camper rig was ideal. I needed to be self-sufficient and able to camp off-grid. During my trip, I didn’t go to any stores and I never went into any buildings other than the dams. Gas stations were it.

Above: The Toyota and Four Wheel Camper rig near Pasco, Washington on the Snake River. Photo Credit: Tight Line Media

How did the rig finally come together?

There were two important adjustments. My truck’s bed is 6-feet but the Four Wheel Camper Hawk worked better aesthetically with a 6.5-foot bed. Toyota had to bring in a different truck, which they also brand wrapped.

We also added airbags to balance the camper’s weight. The dealer changed the charging ports for me. On a Toyota, you can’t charge anything once the truck is off. With my project, I had to be able to charge things overnight. Those ports allowed me to charge my gear when the truck was off. The solar on the camper was a lifesaver.

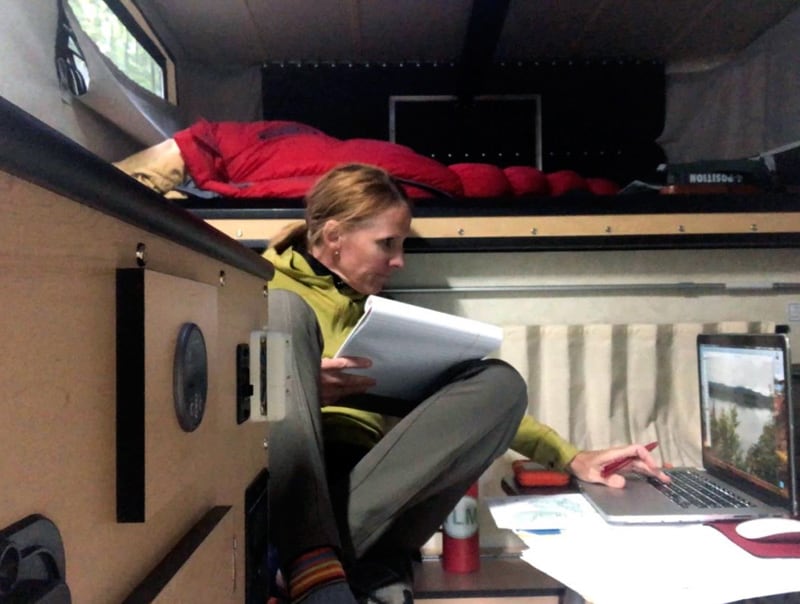

Above: Kris Millgate working inside the Four Wheel Hawk after being out on location all day. Photo credit: Tight Line Media

I’d shoot all day with all different cameras. Then I’d return to the camper, import the pictures and footage into my laptop, and charge the batteries for my cameras and computer. On the Oregon coast, I had to use the camper’s heater. The heater uses a good amount of battery power. Fortunately, the camper’s solar panel system kept the batteries charged.

The solar and battery set-up was perfect for working on the road. I was able to use the low water drain to fill my water bottle between shoots. I could also open the refrigerator without popping the top.

I just got back from my final shoot last night. I now have my final footage of the last fish. My complete trip was 4,686 road miles.

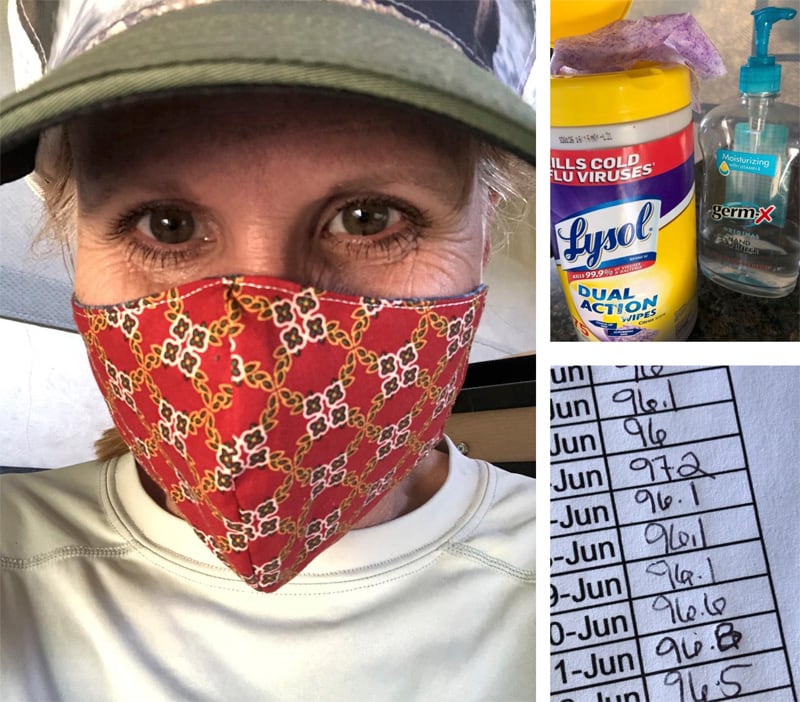

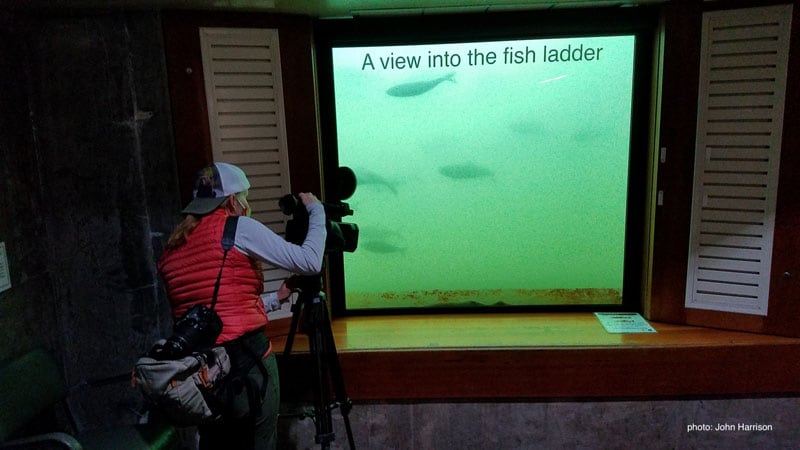

Above: Tight Line Media CEO, Kris Millgate, had clearance to shoot footage at Bonneville Dam in Oregon while it was closed due to COVID-19 restrictions. Millgate wore a mask, sanitized all equipment, and documented her temperature daily while traveling solo and isolating in a truck/camper combo. Photo Credit: John Harrison

That’s an amazing accomplishment. How did your interviews go?

I had interviews at various locations lined up in January. Then, everything was on hold due to Covid. Of particular concern was the US Army Corp of Engineers. They are in charge of the dams and were closed due to the pandemic. If they remained closed, my film project would go nowhere.

Once the Bonneville Lock and Dam was open, and the Corp of Engineers said that I could go, I was able to get all the other interviews back on board. When I got to Bonneville, the corp met me with masks on, temperature checks, and sanitizer. There was no one around except for the people I was interviewing.

Above: Ocean to Idaho, Mile 432

At Bonneville, I was escorted everywhere. I was the only one at the fish viewing area. I started the trip looking at the Pacific Ocean and I was the only person there. Nothing was open. I was in a new part of the country with new people, but I couldn’t shake hands or be near them. It was a weird feeling.

Above: The Ocean to Idaho rig stationed nicely on a bluff above the Snake River near Pasco, Washington for a few days during field production. The Snake River is one of four rivers Chinook salmon swim to reach their spawning grounds in central Idaho wilderness, 850 miles from the ocean. Photo Credit: Tight Line Media

Do you think being in the truck and camper made a difference to the project?

Through this experience, I realized that a truck and camper are way more efficient than hotels. I really liked traveling without hotels. It gave me a better feel for the locations and people I was learning about.

If it weren’t for coronavirus, I would have had a driver so that I could sleep, work on things, or be on the phone for interviews. By myself, I was either driving, interviewing, working, or sleeping. You can’t do more than one thing at a time. After a while, I figured it out and managed okay. I got wrapped up in the project, so I didn’t get lonely.

Above: Ocean to Idaho, Behind the Doodle

Did you have a plan as to where you would camp ahead of time?

I studied my route for weeks. I studied the river and where the salmon were migrating. I lined up safe areas to stay so that I didn’t need to be on the side of the road. I had to get creative.

Some of the places were closed boat ramps, empty fields, private lots, vineyards, dirt roads, and driveways. I would drive in at sunset and dash out at sunrise. I called these destinations, “Drive and Dash”.

Above: Kris relied on D&Ds instead of B&Bs while on the road during a pandemic. D&Ds are pre-arranged, safe places to park overnight. Millgate calls them D&Ds because she drives in at sunset and dashes out at sunrise. Her hosts often don’t see her, but offer up their empty fields, open driveways, and closed boat ramps like this ramp near Cascade Locks, Oregon. Photo credit: Tight Line Media

Some of the Drive and Dash places came from other reporters and people who follow my posts. As I was lining up the interviews I’d ask, “Who do you know in this area who has a closed boat ramp or a field I can stay in?”

One person would post, “Here’s where my daughter lives. She has an empty field.” And I’d have a safe place to stay the next night.

I didn’t want to spend daylight looking for spots. I wanted my husband and my interviewees to know where I was going to be each day. For safety, I made sure that an interviewee or the Drive and Dash hosts knew I was showing up that day. If I didn’t show up, someone could sound the alarm.

When I arrived, I would text my hosts or they would come out just to make sure that I had arrived and that I was safe. It was a lonely way to travel, but I had no distractions. I often worked 15 hours a day.

Above: Ocean to Idaho, Behind the Rig

What did you think of the Four Wheel Camper?

The camper was simple, durable, and very functional. For what I was doing, it was perfect. I think our travel trailer is better for the whole family, but the four of us did try camping in the Four Wheel Camper near home. That was fine for a night or two, but I wouldn’t want to go for a week or longer.

At home, the boys would go out and hang out in the camper. One of my boys wants to live in one – like an apartment – when he gets older.

Tell us about the dams the salmon face during their journey.

I want to lay all the facts out there and let the viewer decide what they think. You can decide if the dams should stay or go. You will see both sides of the issue in the film. That was done consciously.

I want to show the migration accurately and give you many different perspectives from different people. I wanted to talk to people who had a vested interest in the water and the fish. That started by calling and telling them about my route. I asked who they thought I should talk to and got a consensus. Then, I would survey and whittle my options. Through that process, everything came into place.

Every single person I interviewed for this project, except one person I met at the end, was a total stranger before the project began. As a journalist when I’m going to cover an issue I want to fairly cover it. I had to have perspectives from everyone.

Above: Outdoor journalist, Kris Millgate, uses five cameras when she’s on assignment for natural resource stories like salmon migration from the ocean to Idaho. She documents people and places with a video camera, a photo camera, her phone, a drone for aerials, and a waterproof camera for underwater shots of fish. Photo Credit: Ken Sullins

It can be challenging to avoid being pigeonholed for having an agenda, especially when you cover topics that are potentially political. How did you handle that challenge?

I have covered natural resources in the outdoors for two decades. I tell the people I interview, “It’s not about what I think. It’s what you think, and that’s why I’m asking you”. My goal is to collect all different perspectives about the issue. If someone denies me the interview, it’s their loss.

I want to show everyone about the fish and their journey. When Toyota and Four Wheel Campers came on board I told them I needed editorial control because that’s what journalism is about. That has to be separate from what they want.

That can be risky for them. What if I did an anti or pro dam video? They want to know upfront who they are partnering with, but they don’t dictate what I report on as a journalist.

Above: Ocean to Idaho, Mile 850

From the clips on your website, it sounds like very few salmon make the 850-mile journey. How many salmon successfully make the trip?

That was one of the hardest statistics to find out.

Based on historical counts and the habitat where the salmon could make it, Idaho can host about 127,000 Chinook salmon a year. The last dam is called the Lower Granite and is located on the Washington and Idaho border. Every fish that clears that dam is successful. That’s Idaho’s goal.

To be taken off the endangered species list, 31,750 Chinook salmon have to pass the Lower Granite dam. The number of wild spring Chinook salmon in 2019 was 5,162. That’s how far off we are. When the film comes out next year, the 2020 count will be higher, but not by much.

The Yankee Fork is the last of four rivers they have to travel. It’s where they go to spawn and where they are now. The last count from Shoshone-Bannock tribal researchers in the Yankee Fork was only 29 Chinook and the potential for 13 or 14 spawning beds.

Above: Kris’s film coming out in 2021 will follow the journey of the Chinook salmon, credit: Ken Sullins

How do they track the Chinook?

Some of the Chinook are tagged and can be tracked by detection wires at the dams.

One particular fish I followed left the Yankee Fork in October of 2017. He was marked there and subsequently made it to the ocean. We know this because he showed up on the migration route this year. He reached the Bonneville Dam on May 9th.

Then, he swam past Yankee Fork’s detection wire on July 5th. The tag pings when he gets to certain points on the river. The males will just hang out and won’t do anything until the females give a signal. At the end of August, the spawning happens. At that point, they are still living off of what they were eating in the ocean. They don’t eat for the entire 850-mile trip.

How is that possible?

They are built to make this journey. They have enough nutrients to do it. The fish that start in Idaho will go to the ocean, but most will not make it there. The amount of Chinook that make it back is a small margin.

How long will your film be?

It will be a short documentary. As of now, there are two PBS affiliates that are interested in it. The film will debut in 2021 when the fish return. In addition, there are newspapers and magazines that I’ll write articles for.

The editing will be the least of my worries. Because of Covid, there will probably not be a traditional film tour. How we promote the film will be interesting.

Above: The osprey Kris saved, Photo Credit: Tight Line Media

During your Ocean to Idaho experience, you saved an osprey. Tell us how that happened.

I am a certified Idaho Naturalist and had to take many education classes. Once you’re on the list, you come up for volunteer projects. If a bird gets injured, they need someone to recover and deliver them to rehabilitation facilities. They send out an email asking people to transport the animals to the hospital. For an injured osprey, I was at the right place at the right time.

On my way to the hospital with the osprey, I got pulled over. The police took my license and ran a check. I told him that I had a wild bird in the back and he just gave me a warning.

The very first day I was at Bonneville Dam I watched an osprey eat a salmon. Then, at the end of the project, I was saving an osprey that was hurt. That was pretty surreal.

Above: Duct tape got her through but unfortunately, Kris’s camera will need to be replaced. Photo Credit: Tight Line Media

That might be the first time anyone flipped a bird at the police and got off with a warning. Did you have any other challenges during production?

Yes. My camera broke. That was terrible. The wind grabbed my camera and threw it in the dirt. The lens didn’t crack, but the focus ring and lens hood did. I gathered the broken parts and duct-taped them around the lens to keep it protected, but it was an expensive accident.

That was a huge chunk of money that I was not planning on spending. Nobody has large margins. Since it happened in the middle of my trip I was lucky to have other cameras in the mix that I had to lean on more.

What did you learn about the salmon that you didn’t know before?

There were a lot of things that I learned about them. The estuaries that hold fish are a mix of fresh and salt water. People think the salmon go straight through, but that’s not what happens. The estuaries are like rest stops where they take a break. I also learned that the females make the spawning beds and the males just hang around.

I continue to be fascinated that the Chinook can find where they are born, 850-miles up river. That is mind-boggling. I left my home base and went to the coast. But, I used an enormous amount of technology to get there and back. They have no technology and they can still find where they need to go.

“Just to witness it, not to see it as a journalist, but see it as a human and experience that moment was amazing.”

Do you have any other projects lined up for the future?

I have a few ideas that I’m rolling around. This one took several years and a lot of people saying no. I hesitate to say what is next right now.

I have a feeling there will be more people saying no before I decide what to do. I don’t use can’t or quit or unless I can use them together – can’t quit.

There is a lot of rejection that comes ahead of this process. If it has value and matters, I will stick with it until we can pull it off. I know what I do next will be outdoor and natural resource-related, but probably not with salmon.

I was on the road from mid-June until September 8th. During the last few weeks, I was on call for the salmon spawning. They take one to two days to lay their eggs and then they die. So I drove three hours from my house to the Yankee Fork when it was time.

Yesterday was the last day of my project. I saw a Chinook salmon in the water and just stopped. It’s unbelievable that they make it to the Yankee Fork. I just watched because I felt so privileged to experience it and see it.

At that point, they were starting to decay and they are swimming slower. They know what they need to do before they die. Just to witness it, not to see it as a journalist, but see it as a human and experience that moment was amazing.

The resilience of the wild is what everyone wants to aspire to, especially right now.

Follow the entire salmon migration from the ocean to Idaho by catching Kris Millgate’s road trip episodes on her You Tube channel – which includes many more videos.

To visit the Four Wheel website, go to fourwheelcampers.com. Click here for a free Four Wheel brochure.