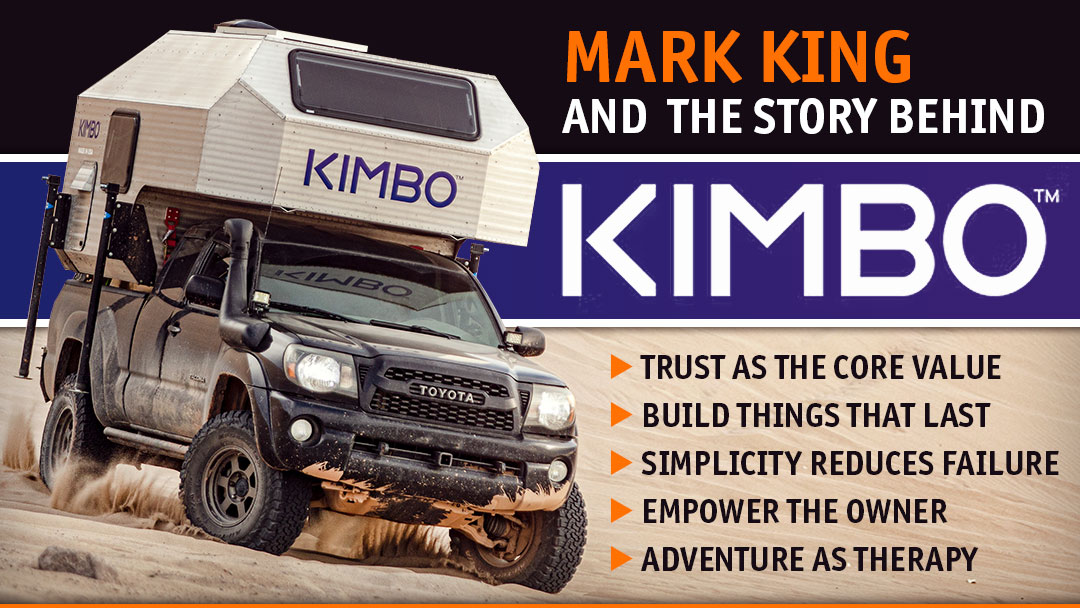

Mark King’s journey to Kimbo Campers runs through nuclear submarines, a multimillion‑dollar metal wallet company, and a Harvard MBA. The result? A camper unlike anything we’ve ever seen before. Get ready to dive into Kimbo!

Mark King’s life has been a story of relentless curiosity, hands‑on invention, and a drive to build things that last. Born in Annapolis, Maryland, to a U.S. Navy submarine captain and Naval Academy instructor, Mark spent his childhood moving between bases across Europe and the United States before his family settled on Bainbridge Island, Washington.

There, he discovered his passion for making things. He learned to weld at fifteen and created everything from PVC potato guns to a high school electric car that earned him free campus parking. By his late teens, Mark was an Eagle Scout and had already filed his first patent.

After high school, Mark pursued machining at Bellingham Technical College, leading to a breakthrough at age twenty-one: developing an organoleptic analyzer for General Mills. A year later, he founded Trayvax Enterprises in his Bellingham studio apartment, hand‑assembling metal wallets designed to last a lifetime. Within a few years, Trayvax was selling hundreds of thousands of wallets worldwide.

Mark’s ventures only grew bolder. Inspired by the efficiency of submarine interiors and his love for the outdoors, he built his first truck camper in 2016 and lived in it for months as he explored America’s national parks. That prototype evolved into Kimbo Campers; rugged, all‑aluminum truck‑bed homes designed for longevity and self‑reliance.

You cannot fully understand and appreciate Kimbo truck campers without first learning Mark’s story and what drove him to build both the camper and company. To get that story, we spoke to the man himself; Mark King, Owner and Founder of Kimbo Campers.

Above: Mark King, Owner and Founder of Kimbo Campers, in a Kimbo prototype

Click here for a 2026 Kimbo brochure

What’s your background and how did you get into manufacturing?

I grew up on Bainbridge Island in Washington, so there wasn’t a whole lot to do. When I was pretty young, I learned how to make, fix, and build things. I used to make anything that I could think of. I’d go to the local ACE Hardware, buy some PVC pipe and make potato guns—stuff like that.

I learned to weld at fifteen and that translated into meeting people who taught me machining work. I made all kinds of things, including a helicopter with a lawn mower engine. In high school, I made an electric car and electric motorcycles. I ended up doing a TED Talk on the electric car.

When you dream something up and then learn how to bring it to life, it’s really rewarding. That process motivated me and still does to this day.

“When you dream something up and then learn how to bring it to life, it’s really rewarding. That process motivated me and still does to this day.”

How did you learn to weld at fifteen?

I just jumped in. I’d ride my bike to the hardware store constantly, piecing together small projects. Eventually, I got a job there. One Christmas, they had a welder for sale, and I thought it was amazing—you could fuse metal stronger than epoxy. I decided I had to learn; but the one I bought was pretty cheap.

One customer, who was always buying nuts and bolts for his projects learned about my curiosity for welding, invited me over and taught me how to TIG weld on a better machine. My dad picked me up one day and this mentor shared some encouragement about the path I was on. My folks were glad I had found something constructive to do.

Above: Mark King’s TED Talk at age 23 on his electric car

What inspired you to make an electric car?

The parking at the high school was $240 a year. I didn’t have that, so I talked to the head of the school and asked, “Why is the parking so expensive?” The reason was to encourage students to carpool, and to be more green. That got me thinking about how I could be the most green. I went back to the head of the school and asked, “If I build an electric car, can I get free parking?” It took me nine months to build the electric car, and I got my free parking. That was my senior project.

You went on to earn an executive MBA from Harvard. Was that after high school?

No. I did everything backwards. After high school, I went to Bellingham Technical College and earned a machinist’s degree. When I was twenty-one, I created an organoleptic analyzer for General Mills through their G-WIN innovation program. That project earned me nearly $20,000 — enough to start my first company, Trayvax, at twenty-two.

Trayvax made metal wallets and gear that were built to last. I started the company in my apartment, moving my bed to a loft and having two shifts of employees that I found on Craigslist help assemble and sew. After an initial Kickstarter campaign, Trayvax quickly grew from four to seven to seventeen to thirty-seven people. We were selling product all over the world and have now sold millions of wallets.

Then I started building the first Kimbo truck camper in 2016. Trayvax and Kimbo were located right next to each other and, including contractors, had seventy employees. When you have that many employees, you are reminded of your blindspots. In the face of challenges, you can make excuses, or you can become a better person. I needed to up my leadership game and so I applied to Harvard, using the companies as a qualification to be accepted.

I had lived out of an Airstream and a Kimbo camper at the factories up to that point before I headed to Harvard. I purposefully kept myself uncomfortable. If you satiate yourself with comfort, your pursuit decreases. You don’t have the same reason to continue to push forward.

Above: A Kimbo 6 truck camper

Did you find what you were looking for from Harvard?

When I was at Harvard, they asked me about my purpose and what I wished to do outside of work. I told them I wanted to build a log cabin. My professor encouraged me to do it.

After graduation, I went to Vermont, bought twelve acres, and built a log cabin. I graduated on June 2nd and started building the cabin on June 4th. I built the cabin by myself in seven months and recorded the experience.

That was really cool. When you push yourself hard for a long time in business and in life, you can start to buckle. Through building the cabin, I found some peace and respite.

When I came back from Harvard, I was ready to be exposed to the next phase of my life. I wanted to step back into it with what I had learned.

Your father was a captain on a nuclear submarine. How did that impact you?

I have a very clear memory of being five years old and driving with dad in his beat-up pickup truck. We arrived at the naval base and there were four men with machine guns. They lowered their guns and saluted my dad. That has an effect on you as a kid.

He was away for four to six months. We couldn’t talk to him. We knew he was serving our country, but we didn’t know where he was. We also didn’t know if he would come back. Over those four to six months, I’d put even more effort into building something. I wanted to show him what I’d done when he came home.

Almost everything he did was secret. To this day, most of it is classified. Over the years, seeing his leadership and the abilities he has inspired me.

When you see a submarine, you never forget it. It’s an unusual thing to experience. It’s built from billions of dollars of engineering. It’s compact and orchestrated in one space. A submarine has its own nuclear power plant. It can run itself for like 30 years without fuel. It’s incredible. They don’t allow the public on submarines anymore, but this was pre 9/11.

Being inside a nuclear submarine as a kid must have been beyond amazing.

It was amazing to see how they sustained life without windows under the ocean for months at a time. It had oxygen and water regeneration systems. The only thing they can run out of is food. I was able to go around and see how every space was multi-functional. As someone who’s mechanically oriented, I was curious about everything.

At the time, the submarine was like the ultimate tree fort. When you’re a kid and you have your first tree fort, you want to hang out in it. The more deluxe you make your fort, the longer you want to stay out in it.

Our Kimbo campers are cozy self-contained cabins that go on the back of a truck. It doesn’t feel like a normal camper. It’s designed for self-sustainability. It’s definitely inspired.

Above and below: Inside a Kimbo 6 truck camper

Kimbo is also a very unique design. Where did the Kimbo design and concept come from?

I wanted to build a camper that I trusted and knew would last. I was looking at campers on the market and wasn’t impressed with their quality or reputation.

I wanted to build a camper that had longevity built into it. If you look at Trayvax, the products are well-built, and they last. The longer something lasts, the more it can be used and relied on and trusted. Our products need to be that way. Too many products are designed to fail, so you purchase another one. I want to spend my life building things that last.

“The longer something lasts, the more it can be used and relied on and trusted. Our products need to be that way.”

I took the first Kimbo camper concept out for tens of thousands of miles. I went to the national parks for the first time. I got to see the edge of the Grand Canyon, the ocean, and I spent time with God. I got to truly see the world for the first time. There are people who will travel to hot spots of other countries, I’ve done it too. But there are so many incredible places within this country that feel unmatched.

When I set out on that trip, I was really tired. I had worked my twenties away. I never got to explore the world. On that adventure, I found a new purpose. I wanted other people to go out with their families and do the same thing I was doing. I was motivated to take the camper and turn it into a business.

So you left tired and returned recharged and ready to start Kimbo?

Yeah. I wanted to bring the experience of seeing the national parks to more people. For many, it’s hard to get away from the feeling of safety that keeps them at home. Uncertainty is demotivating, so people stay at home and make dreams to head to new places.

I bet you know this feeling well. You’ve been at home for months and you’re getting things ready for a trip. You start driving away from your house. At that point, you are leaving something behind and going somewhere new.

Having a camper that you can trust and rely on makes the leaving part easier. I want more people to see the national parks, meet new people, and create new experiences and stories.

How did you go from building a single prototype to launching Kimbo campers?

After returning from my trip in the prototype, I started designing a version that was manufacturable. That forced me to look at it from some different perspectives. Using CAD, I designed and built a second, then a third, and finally a fourth prototype. With each iteration, I did a lot of testing.

There’s this principle—immerse yourself and verify innovation. With anything I come up with, I have to be the first to build it so I can experience the manufacturing pain points. All along the way of building and designing a product, it should be optimized for production. I also tested and experienced the camper from the perspective of a customer. I have lived in and used a Kimbo extensively. By doing that, I become the best salesperson because what I say is real and true.

I also looked at Kimbo from the perspective of the viewer. Does it have the network effect embedded into the design?

The network effect?

Too many campers look the same. They are made of the same materials and have similar shapes and graphics. In contrast, Airstream has always visually stood out. When a trailer goes by, your preconscious doesn’t notice it. When an Airstream rolls past, your preconscious notices. That’s the network effect. I looked at Kimbo from that perspective. It’s visually distinct.

It most definitely is. Why did you choose an all-aluminum riveted design with no internal frame?

Campers are exposed to tens of thousands of cycles of heat and cold. If I build an all-aluminum shell and it’s all expanding and contracting at the same rate, it’s not going to separate from itself. That eliminates many of the problems campers can have over their life span.

Starting with a monocoque shell also gives Kimbo more room for insulation. And by not having a frame, you avoid conducting heat or cold into the unit. The result is an interior that doesn’t feel like a camper. It feels cozy, like a home.

“By not having a frame, you avoid conducting heat or cold into the unit. The result is an interior that doesn’t feel like a camper. It feels cozy, like a home.”

How is the insulation in a Kimbo installed?

There are indexed stand-offs on the shell. We then press CNC-cut one-inch foam insulation against the interior of the shell. The stand-offs are threaded with thumb screws and that’s what holds the insulation. There’s no adhesive.

That goes back to an experience I had in the Airstream. The wind was blowing hard at a trailer park I had lived in and a neighbor’s metal pop-up tent whipped into my Airstream, causing a big dent and scratch. Their insurance didn’t pay for it and that lit a fire in me. It wasn’t right.

To make that experience into something positive, I thought about how I could make the Kimbo scratch and dent-resistant. I made the exterior 1/10 inch thick aluminum. That’s difficult to dent, eliminates the need for a frame, and expands and contracts as one. Then I buffed the exterior with a spiral pattern. If the unit gets scratched, it will fade into the spiraled design.

When you’re inside a Kimbo in the woods, it feels cozy and safe. It’s a visceral sense. People may not buy a Kimbo for that feeling, but they’ll definitely realize there is something different about it. The effect of the spaces we’re in and what’s around us is subtle. We often don’t know how to put that sense into words. I wanted the experience of being in a Kimbo to be something owners can trust.

Was system access and maintenance part of the design plan?

Yes. The more complexity there is to the system, the more complexity there will be to the experience. I decrease complexity so I can increase the experience people have.

When I went to get a quote after the Airstream scratch and dent incident, it was $8,000. They said that every rivet had to be drilled out. It was a multi-step process. Then they had to take out the cabinetry, insulation, and adhesive. It was an insane series of steps for something that should be an easy fix. You should be able to take a panel off and replace it. That’s not possible with an Airstream.

When you experience getting a dent in your truck for the first time, it’s disappointing, and it changes that sense of newness that you wanted to preserve. You bought the truck to take care of it. Then something happens that’s often out of your control and it changes the way you have to relate.

The moment your truck gets a dent, you care about it less. Then, it gets a second dent, and you’re even less proud of it.

If you can keep something in good condition longer, you will rely on it longer and use it more often. I made Kimbo easy to repair—often by the owner themselves. I want owners to be able to keep their Kimbos in excellent condition and to stay proud of them like a lifelong investment.

Next: A full deep dive into the 2026 Kimbo Series 6—its design, specs, capacities, and an extensive interior photo tour you won’t want to miss.

For more information on Kimbo Campers, visit their website at kimboliving.com. Click here to request a free Kimbo brochure.